Book: These Bodies Of Water: Notes On The British Empire, The Middle East And Where We Meet

Author: Sabrina Mahfouz

Publisher: Tinder

Price: £16.99

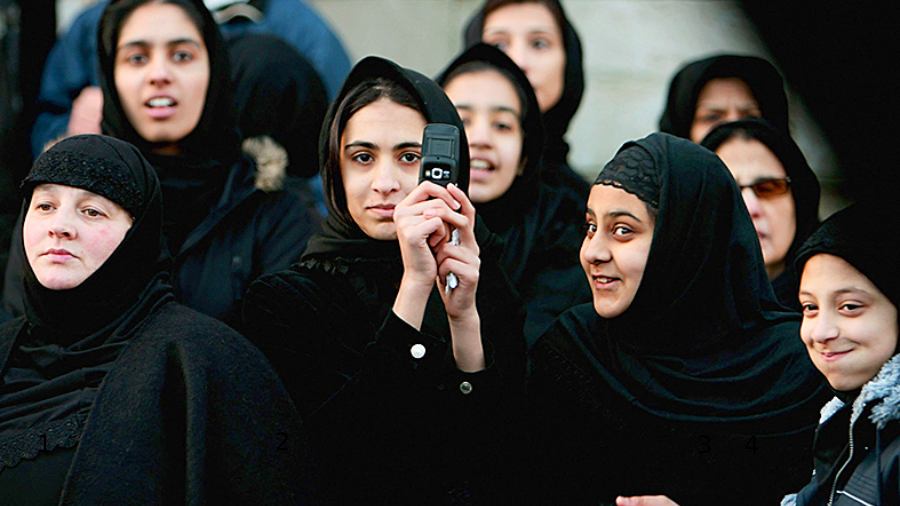

Sabrina Mahfouz, British, of Egyptian extraction, was a successful aspirant to join the coveted higher civil services in the United Kingdom. In 2006, when she joined, she was the only Arab in her cohort. She found she was different in other ways too, being the “only female Arab, the only Middle Easterner, the only mixed Muslim heritage graduate from a lower socio-economic background in a group of 1,000 young people”. For Mahfouz, this was “a sudden and vicious shift to find myself existing purely in opposition”. Mahfouz acknowledges that she got to join the civil service because of the excellence of her schooling in London. Her racially-mixed parentage allowed her to pass as white; an advantage, as she notes: “I was certainly able to code switch in ways that gave me far more access and opportunities than those who could not pass as white.”

Promotions in the ministry of defence required being vetted for a top-secret clearance. This meant a series of detailed interrogations in which all aspects of your personal life, your political attitudes, and feelings were scrutinized and evaluated to assess if you were suitable for expedited promotions. The vetting involved delving deep into Mahfouz’s personal life, including her early years in Cairo, life as an immigrant in Britain, an abusive boyfriend, financial difficulties and so on. There was equally deep probing into how Mahfouz viewed Britain’s record in the Middle East. These questions and how they provoked Mahfouz to study British imperialism comprise the bulk of this book.

The context of this vetting and Mahfouz’s delving into Middle Eastern history is evident: the general culture of suspicion in Europe that surrounded Arabs and Muslims post 9/11 and the Global War on Terror. Mahfouz’s purpose is to show “the colossal breadth of Britain’s imperial projects, invasions and exploitations in the region” and, equally, “how colonization continues to connect us…” For this examination, she looks specifically at the histories of Egypt, Iraq, Yemen, Jordan, the UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait and Palestine. This is a story of imperial intervention in all its different manifestations: political, cartographic, military and economic.

While modern imperialism in the Middle East is usually associated with the demand for hydrocarbons, her particular focus is on how imperial exploitation depended on the manipulation of water resources of the region. That explains the title, “These Bodies of Water”. Hydrological interventions influencing cartographic impulses are a significant part of the history of the first half of the 20th century and remain important in explaining the continuing conflict in the region.

Her main point is obvious enough: that the older colonial and hierarchical relationship between Egypt and Britain and between the Arab world and the West deeply influence her status in Britain today, notwithstanding numerous countervailing forces that may have apparently minimised the weight of history. She narrates a not unfamiliar tale with conviction and clarity and her arguments have a degree of subtlety that acknowledges that much of the critique and the vocabulary of the anti-British imperialism argument are also developed in that country.

Mahfouz was not granted the top-secret clearance and left the civil service. She guesses that the evaluation correctly judged that the knowledge she had gathered meant that “we can never trust you”.

The non-British and the non-immigrant reader may, however, ponder the value of such introspective and searingly honest critiques. They clearly do not dilute the desire of the best and the brightest in many former colonial subjects to emigrate to Britain or to the more powerful United States of America to which the baton was passed after formal decolonisation. Nor, apparently, does the huge body of knowledge about the trauma of imperialism, which has been created in the intellectual and cultural repositories of former colonial powers, actually impact current policies towards former colonies. Perhaps such accounts are no more than a kind of journey of individual self-discovery for the intellectually curious and sensitive emigrant who has had the benefit of a progressive education and exposure in the former imperial metropolis.