How do we see music or visualise sound when we hear it? The recently-concluded In Between the Notes, an exhibition at Experimenter, Ballygunge Place, showed that one does not need to be Wassily Kandinsky to be able to see music. But the eye does need to be trained. This is exactly what the first exhibit of the show was meant to achieve. Thin strips of light illuminated a small, dark room where ragas (Puriya Dhanashree when this reviewer visited) by Pandit Pran Nath — his sonic explorations were the inspiration behind the show — played in a loop. In the darkness, the trance-like repetitiveness of the music, aided by the bands of light near the floor, created varied ‘phosphene phenomena’— patterns such as waves of light that can be seen when the eyes are shut — behind the eyelids. Interestingly, the ragas were programmed to reflect the time of the day so each viewer had a different experience based on when he or she visited.

An artwork by Parul Thacker

With the notes from Pran Nath’s tanpura still reverberating in the mind’s eye with their synesthetic vibrations and cascading overtones, one walked into the room displaying Parul Thacker’s works. Here, the senses are hit by more sounds. Pran Nath’s ragas are still a distant hum, now overlapping with the beats of Lala Rukh’s Rupak spilling in from the next room. (Lala Rukh’s work was not playing when this reviewer first viewed Thacker’s works and a second visit needed to be made to experience this interplay.) This spillage of one aural experience into another is intentionally curated to enhance the delicately embroidered sculptures by Thacker (picture, bottom). At first, the hand-embroidered palimpsests on gauzy silk seem like cartographical charts. In a way they are, but they chart the energy and aural fields of vibration created by music. Lenticular prints and crystals encased in gold leaf aim to capture the sonic reverberations of the cosmos. The shifting, bluish-black shades of the lenticular prints mirrored the granulated interiors of the crystals, both capturing sound waves in a form that the eye could perceive. Thacker collaborated with Isaac Sullivan for these pieces.

Lala Rukh’s Rupak — an animation of dots of white light mapping each tap of a tabla solo of rupak taal across a black screen — was excellently displayed in yet another dark room where the shifting dots of light were the only source of illumination. This makeshift sensory chamber where all but select senses are deprived of stimuli was the perfect setting for Rupak.

From darkness one travelled to the bright light of a snow-capped mountain for Sabih Ahmed and Taus Makhacheva’s Superhero Sighting Society. The scenography conjured up by Super Taus (Makhacheva’s alter ego) includes two icy peaks — the location of Superman’s Fortress of Solitude perhaps? — between which the audience must stand with witness accounts of superhero sightings from all over the world playing in different languages in the static tone of radio despatches. As the ear tries to catch alien experiences, often in foreign tongues, the mind conjures images and apparitions from this cacophony of voices. The message that echoes is this: is there a superhero to alleviate not a cataclysm but the everyday crises of mankind?

From bustling cacophony to funereal silence. Biraaj Dodiya’s works — large stretchers painted in earthy tones — automatically bring to mind the haunting clangs that accompany medical stretchers. The body is absent in the rows of stretches that are hung up like Soutine’s carcass on the sanitised white walls of the cavernous space, but it has left its visual and aural marks, both on the stretchers and in the viewer. Sounds — terrifying wails of ambulances and people during Covid come swiftly to mind — in this chilling exhibit emanate from within the viewer and are amplified by the ambient silence in which the works are displayed.

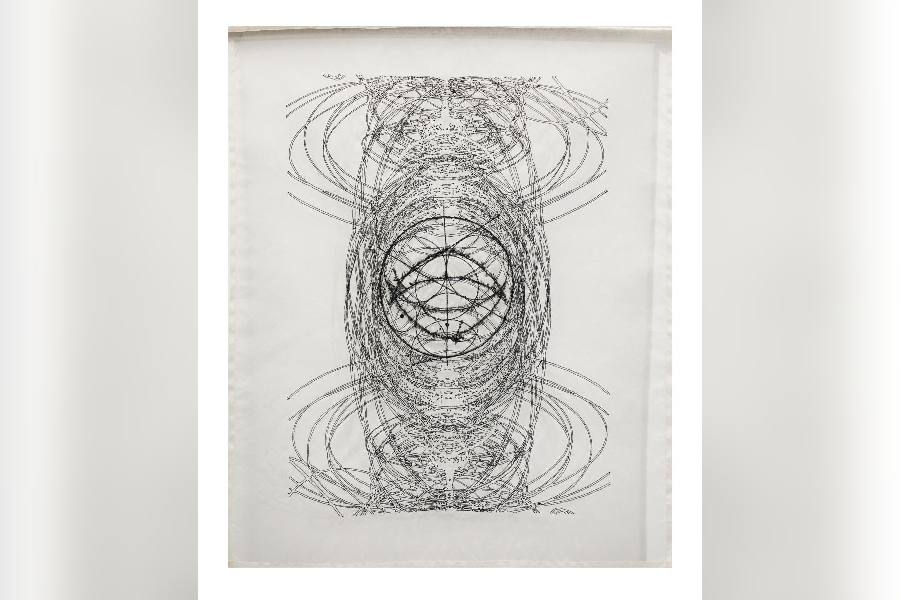

Far removed from these works, in a room upstairs, is Samson Young’s video installation, Music for Specific Places, Times, and People #1. Meant to be heard with headphones, the means of communication of this work is as personal — the noise-cancelling device shuts out the world outside — as its message is universal. Young explores the notions of freedom and agency through his video and small graphic works that accompany it (picture, top).