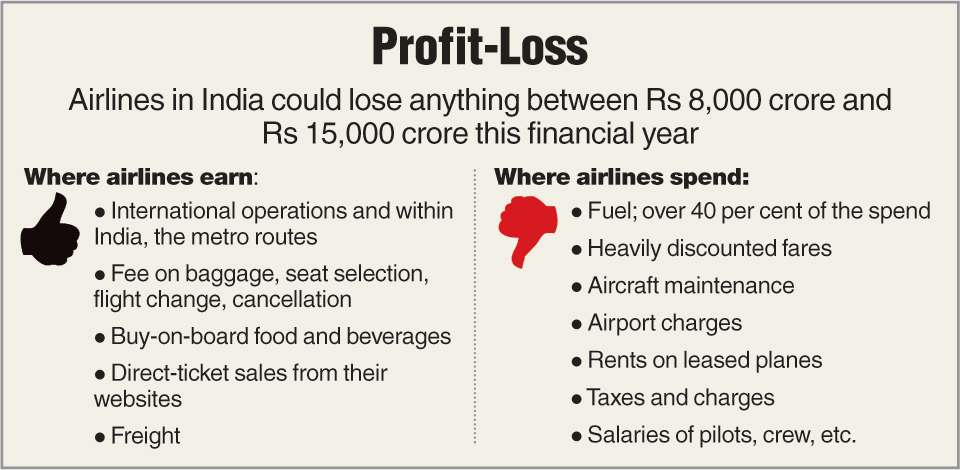

Telegraph infographic

Sometime towards the end of September, an airport was inaugurated at Jharsuguda in Odisha. Jharsuguda is an industrially developed district, rich in minerals and teeming with power plants. According to plan, local carrier Air Odisha was supposed to operate all flights from here. The airport was named after the 19th century tribal leader, Veer Surendra Sai. No less than Prime Minister Narendra Modi was present at the opening. In his speech, he pointed out that Odisha had only one major airport even after all these years since Independence, whereas a district in Gujarat such as Kutch had five airports. He offered more stats — only 450 aircraft operated in the country since Independence, while in the past one year steps had been taken to add close to 1,000 aircraft.

It is true, air travel in India is booming. At the end of March 2009, all Indian airports put together had handled 68 million passengers. This year, to date, Delhi alone has handled that much traffic. And according to the latest report of the Directorate General of Civil Aviation — the regulatory body for civil aviation under the ministry of civil aviation — between January and September this year, domestic airlines flew 10 crore passengers as against 85 lakh in the corresponding period last year. Simply put, a growth of 20.94 per cent, the highest in the world.

But while air passenger numbers are booming, the sector itself seems to be hurtling towards bust.

The real story of India’s civil aviation industry is in the footnotes, not the headlines.

A fortnight after the grand inauguration, the Veer Surendra Sai airport closed down. Reason: Air Odisha, reportedly owned by relatives of industrialist Gautam Adani, refused to operate.

Air Odisha, which is the most complained about airline for flight cancellations in the country today, cited technical reasons. But this is the unique thing about the Indian aviation industry — almost everybody related to it is making big bucks except the airlines.

Owing to rising aviation turbine fuel (ATF) prices, the depreciating rupee and competitive ticket pricing, not a single airline in India is earning more than it is spending. The losses run into thousands of crores of rupees.

It is not as if the big players are denying any of this. Recently, Jet Airways CEO Vinay Dube wrote a letter to the carrier’s privilege members in which he admitted Jet’s net loss of Rs 1,261 crore incurred during the July-September period.

Jet reportedly cannot pay its employees on time, pilots are threatening to stop flying if dues are not cleared and there are reports that Vistara Airways is in talks to acquire it. But instead of following up this admission with even a hint of a plan, Dube lapsed into talk of “encouraging growth” in “key operating metrics”. He did throw in some numbers, but those had to do with increased aircraft count — six brand new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft within the next six months.

It is not just Jet, Air India’s losses are mounting, market leader IndiGo has announced a loss for the first time since it took off in August 2006, SpiceJet is said to be looking for fresh investments to stay airborne. Some new airlines like Air Odisha (of Jharsuguda fame), Air Deccan and TruJet are not flying aircraft on several shorter routes as not operating is a more viable option than flying. In fact, had it not been for the recent fall in fuel prices and the rupee’s recovery, at least two airlines would have come to a grinding halt. They did not have enough cash to sustain themselves beyond a month.

Industry body Federation of Indian Airlines (FIA) has approached the civil aviation ministry asking it to grant airline operators additional time to pay oil companies and airport operators. A civil aviation ministry official told The Telegraph that the ministry will consider the issue.

The aviation industry has always been considered a challenging one as the margin of profit is nominal and at the same time sensitive to unpredictable factors such as fuel prices, recession, wars and so on. “Aviation is a high cost industry and the Indian consumer is extremely price sensitive. You either break even or make marginal profits or run into losses,” says Jitender Bhargava, an industry expert. “Here, everyone is running big losses,” he adds.

Though airlines make marginal profits on international routes, it is domestic travel where they carry the bulk of the passengers. And where they incur losses.

Last year, the central government’s UDAN scheme to promote regional connectivity — under which the airport at Jharsuguda was imagined — did attract a few new airlines. But there was turbulence even before takeoff. An official of a relatively new airline in India tells The Telegraph on condition of anonymity, “We don’t have enough certified pilots in India. The foreign pilots we hire to fly ATRs charge around $15,000 per month. Add to that, fuel and maintenance costs. It is a loss-making proposition from the start. We are better off not flying.”

But the larger problem for the aviation industry remains that almost all airlines, for many years now, have been pricing tickets well below the cost of production of a seat. “You cannot make money when you do that. The heavens will not fall if they increase prices, but they will not do that as they are guided by the future,” says Bhargava.

The future he is talking about is the number of aircraft the airlines have ordered when the going was great. IndiGo alone has ordered around 530 aircraft that will be delivered over the next five years.

Kapil Kaul of the Centre for Aviation (Capa), which studies the aviation industry, says carriers taking delivery of new aircraft will deploy the additions on newer routes to get a larger pie at lower prices. In other words, bigger losses.

According to the latest Capa study, the Indian aviation industry is expected to lose $1.65-1.90 billion this financial year. “And this is only a conservative estimate,” warns Kaul.

Every airline in India wants a larger share of the market pie. Each one is bearing losses in the hope that a competitor would make even bigger losses and become unviable and eventually quit. Air India has been losing its market share but has been bankrolled by the government despite huge losses, while Kingfisher shut shop a few years ago. Eventually, it is said that when fewer airlines remain in the fray, they can come together and control the prices. Something like what the telecom companies tried before Reliance Jio came into the picture.

“It is a dog-eat-dog environment. We can see a bit of consolidation if and only if Vistara acquires Jet. But even that will not help if the competitive environment continues. There is nothing like a low-cost carrier in a high-cost environment. What we have are low-fare carriers and price wars that will kill everybody,” says Ravi S. Menon, promoter of Air Works, one of India’s largest private aircraft maintenance companies.

But talks of consolidation have gone on for nearly a decade now. The operators have remained the same, and now new ones have jumped into the fray. Why are there so many new joinees, notwithstanding the non-existent profits? Says an official of TruJet, “Aviation is a highly visible industry. People recall airlines that collapsed almost two decades ago. That is the kind of recall value this industry has.”

But visibility aka glamour alone cannot be the wind beneath those wings. “You can survive only when you have deep pockets and can run an airline efficiently,” says the TruJet official. IndiGo’s track record was exemplar for a fair while — consistent profits for many years.

IndiGo raised eyebrows aplenty when it ordered 250 Airbus A320 Neos at a cost of $26.5 billion in 2015. When it came to ordering planes, it had broken all records in 2005 and then again in 2012. But it had also shown strategic planning in its choice of aircraft (those with a slim fuel diet), accessories, as well as in-flight crew hires. For instance, instead of stewards, it hired air hostesses, who on average weigh 15-20 kilos less than their male colleagues. As opposed to the bulky seats of other airlines, it got lightweight ones. According to industry experts, these measures saved hundreds of kilos per flight, which were then utilised to carry more freight.

IndiGo seems unlikely to let up its expansion spree even now. In the first six months of this financial year, it added 30 aircraft to its fleet, and plans to add another 50 before March next year. “We believe that the depth of our network, increased capacity and high number of flights provide us with a competitive edge through economies of scale, allowing us to optimise our costs,” says a company spokesperson.

One indicator of how a sector is doing is to look at the share prices of the companies listed on stock markets and almost all the major fliers except for Air India are listed in India. The numbers paint a sorry picture. “They have been wealth eroding stocks for many years now. Shareholders have only lost money. It is a win-win for the passengers and lose-lose for the airlines,” says Sanjiv Bhasin, executive vice-president, markets and corporate affairs, IIFL Securities, a financial services company.

Can the government help in any way? It could, say experts. “The government has done its bit by relaxing foreign direct investment conditions for airlines. It could do more by reducing the tax on ATF or bringing it under GST. It could also bring down the airport landing charges and other taxes,” says Bhargava.

Menon adds that the government could also work towards reducing the costs of airlines when it comes to maintenance, repair and operations or MRO, as it is known in the industry. It seems, because of high taxes in India, many airlines prefer China, the Middle East and even Sri Lanka for maintenance. But why the government should jig policy to help private enterprise is also a fundamental question — running private airlines viably and profitably should be the business of those airlines.

Real solutions should come from within the industry itself. “Unless the airline honchos sit together and decide that they will not sell their tickets at a price less than their cost, they will continue to suffer. They may lose some passenger traffic. But that would be in the interest of the industry. Will they, that is the question,” says Bhasin.

Menon says, “At the end of the day, it is no rocket science. If you are running a business, your income should exceed your expenditure.” But airline operators have been busy killing their competitors rather than worry about their own profits.

Meantime, Jharsuguda languishes after its initial promise. There may soon be a fresh tender for a new operator, but that will be when it will be.