Nana Patekar has a new role. And it's not for a film to be screened in a theatre near you; it's for farmers in rural India. In September, the actor set up a foundation called Naam to help farmers in distress.

It's not an issue that you generally hear Hindi film actors voice their concern over. But this year alone, in Bollywood's backyard, around 1,400 debt-ridden farmers killed themselves. And like many others, Patekar says he followed the crisis but just took it in his stride.

"For years, I watched the plight of farmers and their families on television and then forgot about them," Patekar, 65, says. "But one day I felt that I had lost my sensitivity because I was no longer reacting to the farmers' deaths. That's when I thought of helping them."

Patekar, who has acted in some 60 films, had tucked away Rs 1.5 crore for a luxury car. He thought he would distribute the money among the families of the farmers instead. That was when his friend, Marathi actor Makarand Anaspure, advised him to visit the drought-affected regions before giving any financial help.

"I went to Beed and saw young widows and their children. I realised that I could not fulfill their requirements in my lifetime," he says.

Patekar donated Rs 25 lakh to the families. The media blitzkrieg that followed led to donations pouring in, prompting him to set up the foundation. In less than a month, it had received Rs 9.5 crore. "Even a beggar contributed Rs 300," he says.

Naam, which will soon have branches in several cities in Maharashtra, seeks to create alternative employment opportunities for farmers. It will, for instance, teach families how to weave. Efforts will be made to convince farmers not to take loans for lavish weddings but to have simple weddings.

"We have also told them that we will work for them if they promise not to open any liquor shops in their villages. Also, they should not harbour communal feelings," he says.

Patekar believes that deprivation forces people to take "extreme" steps. "The farmers feel helpless, so they kill themselves. But one day they can pick up guns and target people in power."

That's how, he adds, Naxalites were born in Bengal. "I feel frustrated when I see the huge disparity in our society. If I was not an actor, I would have committed suicide or become a Naxalite," he says.

It is the poor who are affected by every crisis, whether it's a flood or drought or communal riot, he stresses. I ask him about the lynching of Mohammed Akhlaque, a Muslim resident of Bisada in UP's Dadri, by a Hindu mob. "Shame on those who killed the man," he says with scorn.

Patekar rues the changing times. When he was growing up, his family lived in a house where the landlord was a Muslim. "As a child, I never saw any difference between Hindus and Muslims."

He grew up in poverty, he reveals. His father, Gajanand, ran a textile printing firm in Mumbai but an aide sold it illegally. When he was 13, Nana painted posters to earn money. "I had to walk eight kilometres from Matunga to Chunnabhatti for painting posters," he recalls as he fiddles with a gold chain twined with rudraksh beads circling his neck.

"There was a time when I used to visit friends hoping they'd offer me food. Often they didn't," he recalls.

In his interactions with the media, the actor seldom fails to mention the hardships that he and his family faced. Perhaps it helps him to stay grounded. And he would know that the press loves a rags-to-riches story.

Poverty, he adds, made him aggressive. "I often picked up fights with people. I always thought people were letting me down."

It's because of his temper - he wears a yellow sapphire and pearl in a bid to control it - that he says he has stayed out of politics. He has turned down offers from all leading political parties - the Congress, the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Shiv Sena. "I always speak my mind but politicians don't want that. I will be thrown out of any party if I join one."

There's a general perception that he's close to the Shiv Sena. Patekar explains that he had an "extremely special" relationship with the late Sena leader Bal Thackeray. He became a fan of Thackeray's political cartoons when he was studying commercial art in the JJ School of Art. "He was like a father figure to me," he says.

Thackeray stepped in when actor Tanushree Dutta accused Patekar of misbehaving with her during the shooting of the 2008 release, Horn 'OK' Pleassss. Thackeray had apparently then asked film producers to blacklist Dutta. "He was always very protective of me," Patekar says.

But he doesn't have much patience with Sena antics - such as its recent move to stop a concert by the Pakistani singer Ghulam Ali in Mumbai. "If I meet Uddhav (Shiv Sena chief), I will tell him that I didn't like this," he says.

Ghulam Ali holds a special place in Patekar's heart. The actor had an accident during a shoot and was laid up in his Pune house for a while. One day, Ali paid him a surprise visit. "He asked me, what do you want me to sing. I said, anything. Then he took the harmonium and started singing one of my favourite ghazals, Kal chaudvi ki raat thhi. His voice healed my pain."

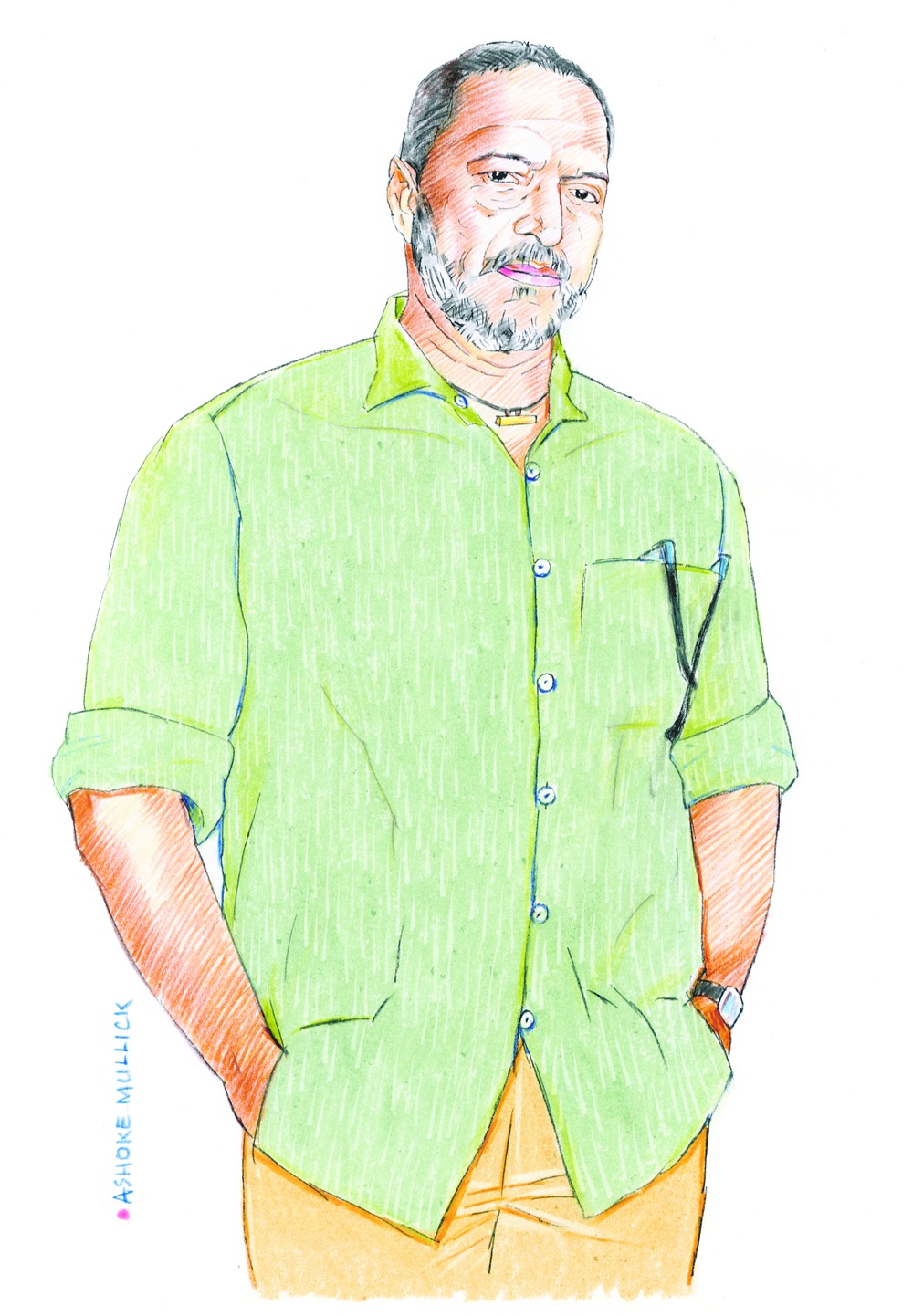

We are sitting in the same flat in Pune's Ashok Path. Patekar is dressed in a white kopri (a sleeveless shirt with a pocket at the centre) and a pair of yellow shorts. The room is as casual as the actor - it's sparsely furnished with four wooden chairs, a couch and a dressing table. The man who has seen poverty from close quarters is now the proud owner of five houses in Mumbai, Pune and Goa. He guides me to the first floor of the house and the terrace, and points to a huge bathroom - as big as a room. He wanted it big because he felt claustrophobic in their tiny bathroom when he was a child, he says.

Patekar has not just made money; he has earned recognition as well. Fond of theatre, he was working with an advertising agency as a commercial artist and visualist when actor Smita Patil persuaded him to try his luck in films. His first film was Muzaffar Ali's Gaman (1978). He has acted in a great many hits such as Parinda (1989), Tirangaa (1993) and Krantiveer (1994).

Critics hail him as a natural actor, for he is known to make reel life character appear real. In fact, for Prahaar, a 1991 film that he directed as well acted in, he trained with the Maratha Light Infantry for over two years. "That's my favourite movie," says Patekar, who has a firing range in his house.

Another of his favourites is Agni Sakshi (1996), where he played Manisha Koirala's possessive and abusive husband. I take the liberty to ask him about his off-screen romantic relationship with Koirala. "It was an amazing time of my life. But now she is happy somewhere. So that's fine," he says.

He has a good rapport with many of the industry's leading lights. With Amitabh Bachchan, in particular, he shares a warm relationship. He recalls how, when they were both shooting for Kohram (1999), Bachchan one day announced that his daughter had given birth to a baby boy. "I have become a nana (grandfather)," he said. "To this, I replied: Aapko itne din lag gaye Nana banne mein? Main toh bachpan se hi Nana hoon (It took you this long? I've been Nana since the beginning)."

Nana, however, is not his original name. He was named Vishwanath but one of his mother's friends used to fondly call him "Nana" when he was a child. "So I became Nana," he laughs.

In the middle of the conversation, he suddenly leans over and asks me to tie a red thread that's come loose on his wrist. " Tera miya kya karta hai (what does your husband do)," he asks casually. When I tell him that I am not married, he wants to know how old I am. Why didn't you get married, he asks.

His own marriage came apart seven years after he and Neelkanti, a Marathi writer and actor, were married in 1978. "We live separately but we meet often," says Patekar, who lives with his 95-year-old mother, Anusuya.

His relationship with his wife, he reveals, became strained after their first child was born physically challenged. "I couldn't believe that my son could be born with such physical deformities. I blamed my wife for that," he reflects.

His son died when he was two-and-a-half years old. Five years later, Malhar was born. Malhar has just graduated from New York University and is likely to take over Patekar's production company, Gajanand Chitra.

Patekar would then spend more time with his foundation. A voracious reader, he also writes poetry. He recites a poem as I prepare to leave: " Ghar me bas hai chhey hi log. Chaar deeware, chhat aur main - There are just six of us at home: the four walls, the terrace and I."

A loner, he believes that he will die a sudden death. "And my intuition is very strong," he says.

Not yet, I tell him. The farmers need him.